夫诸。《山海经》中记载的异兽,外貌像白鹿,有四角,它的出现预示着即将发生水灾。夫诸[fū zhū] is a kind of mythical creature in records of the ShanHaiChing, it looks like white hart with 4 horns, it has signaled imminent flooding.Artist:Sheep

夫诸。《山海经》中记载的异兽,外貌像白鹿,有四角,它的出现预示着即将发生水灾。夫诸[fū zhū] is a kind of mythical creature in records of the ShanHaiChing, it looks like white hart with 4 horns, it has signaled imminent flooding.Artist:Sheep

Sinosphere is a very real term. It doesn’t mean that China is the strongest and the best. It just means that this is a sphere of influence that was started by Chinese culture.

Every aspect of Chinese culture was adopted by surrounding countries, just like how modern people adopt American ways of life, down to the language, clothes, food, and entertainment. Chinese arts, language, food, and fashion were spread throughout East Asia. However, the ones most influenced by this cultural power were Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Ryukyu was also part of the Sinosphere, but was later absorbed by Japan.

To put things in simple terms, all of these 3 nations started their borrowings during Tang. However, by the start of westernization:

- Japan is most influenced by Tang and Song cultures. (Japan stopped borrowing from China once Yuan dynasty appeared)

- Korea is most influenced by Yuan and Ming cultures. (Korea stopped borrowing from China once Qing dynasty appeared)

- Vietnam is most influenced by Ming and Qing cultures. (Vietnam continued to borrow from China until French colonization)

Source: lilsuika

It’s out!

I illustrated for Disney’s MULAN book “Mulan’s Lunar New Year”, (you can see the book here!) a children’s book about little Mulan spending Lunar New Year with her family.

It’s my first book and I want to share some illustrations 😀 [*will also have this book at my table at CTNx 2018 this year on display at T55!]

Looking back, there are lots that I want to improve on the crafting of my drawings for this book, but overall… I’m really glad I get to illustrate and to remember the joy and excitement I had celebrating Lunar New Years and lighting fireworks with my parents as a kid.

It was pretty magical.

Hi, thanks for the question!

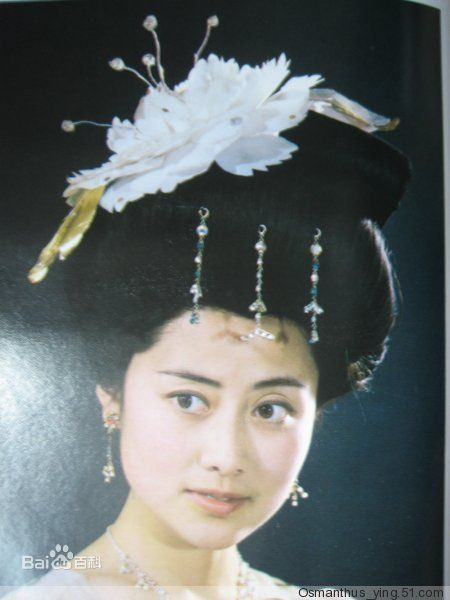

The painting you’re referring to is the famous Tang dynasty hand scroll by Zhou Fang, “Court Ladies Wearing Flowered Headdresses/簪花仕女图”. This scroll depicts five palace ladies and a maidservant amusing themselves in a garden.

The court ladies’ hairstyle is called Gao Ji/高髻 (High Ji), also known as E Ji/峨髻 (Lofty Ji). “Ji/髻” refers to any hairstyle involving pulling hair on top of the head. Gao Ji was a popular hairstyle among Chinese women during the Tang dynasty. As its names indicate, it refers to a relatively high and full updo, decorated with hair ornaments. Tang culture celebrated fullness and glamour, and that aesthetic extended to hair as well. Tang women believed the higher the hair, the better, with some using wigs to achieve the desired look – it was not uncommon for the updo to reach over one foot in height. Gao Ji was beloved by all classes of women during the Tang dynasty.

Gao Ji came in several different varieties. The specific one you’re referring to, with the peony pinned to the top, is called Zan Hua Gao Ji/簪花高髻 (Flowered High Ji). This style involved a Gao Ji embellished with huge peony or lotus blossoms, as well as gold hair ornaments.The practice of wearing flowers expressed women’s admiration for the beauty of the blossoms, but also symbolized the fleeting nature of youth.Zan Hua Gao Ji was especially popular among aristocratic women during the Tang dynasty.

Here are two modern depictions of the hairstyle:

Regarding the court ladies’ outfits – the relatively low neckline and nearly floor-length sleeves of the gowns, and the wide gauze scarves worn as stoles or draped across the arms, are all characteristic of the high court fashion of the Tang dynasty. I also addressed the same question in my reply to you here, so please check it out.

Hope this helps!

Eighty-seven Immortals (八十七神仙卷) by Wu Daozi (吳道子). Ink on silk handscroll. ca. 685–758 BCE.

Wu Daozi was a master painter of the Tang Dynasty. Born in the Henan province of China, Wu lived from circa 680 BCE to circa 760 BCE. Throughout his prolific career, Wu painted many Buddhist and Daoist murals. Wu was given the name Daoxuan by Emperor Xuanzhong after gaining appointment to the imperial court as the official painter. Due to Wu’s sage-like status in Chinese art history, critics regard him as divine and much of his life history intersects with myth and legend.

“八十七神仙卷” translatets to “eighty-seven immortals,” or “eighty seven celestial people.” During the Kaiyuan Era, reigning Emperor Xuanzhong allegedly commissioned this intricate piece to Wu for his recently-passed mother. The top image is the full scroll, and the following three images allow a closer look at the painting in three segments. An exemplary model of traditional 白描 (baimiao) style, which referes to an ordinary or plain painting style, the piece now resides in the Xu Beihong Memorial Museum in Beijing.

Follow sinθ magazine for more daily posts about Sino arts and culture.